Henry Laurens Chapter five by Stanley L. Klos author, President Who?

Forgotten Founders

Henry Laurens

2nd President of

the Continental Congress

of the United States of

America

Served November 1, 1777 to December 9, 1778

About The Forgotten Presidents' Medallions

© Stan Klos has a worldwide copyright on the artwork in this Medallion.

The artwork is not to be copied by anyone by any means

without first receiving permission from Stan

Klos.

U S Mint and Coin Act - --

Click Here

The

First United American Republic

Continental Congress of the United Colonies Presidents

Sept. 5, 1774 to July 1, 1776

Commander-in-Chief United

Colonies of America

George Washington: June 15, 1775 - July 1,

1776

The Second

United American Republic

Continental Congress of

the United States Presidents

July 2, 1776 to February 28, 1781

Commander-in-Chief United Colonies of America

George Washington: July 2, 1776 - February

28, 1781

Henry Laurens

was born March 6, 1724 in Charleston, South Carolina and died there on December

8, 1792. His ancestors were French Protestants who

were members of the Reformed Church established in 1550 by John Calvin. They left France at the revocation of the edict of Nantes and migrated to the

British American Colonies.

Laurens, the

son of John and Esther Grasset Laurens, was educated in Charles Town, South

Carolina. Upon “graduation”, through the contacts of his prosperous

father, he accepted a position at a local counting-house. In 1744 Laurens

accepted a similar position in London to further his career in the promising

field of international business. Upon his return in 1747 he opened an import and

export business in Charles Town. Through his London contacts, Laurens entered

into the slave trade with the Grant, Oswald & Company who

controlled 18th century British slave castle in the Republic of Sierra Leone,

West Africa known as Bunce Castle. Laurens contracted to receive slaves from

Serra Leone, catalogue and marketed the human product conducting public auctions

in Charles Town. Laurens also engaged in the import and export of many other

products but his 10% commission from the slave auctions proved to be his major

source of his income.

By 1750, Laurens was wealthy enough to win

the hand of Eleanor Ball, the daughter of a very wealthy rice plantation

owner. Laurens, who was also a rice planter, used his auction profits to

purchase exceptional South Carolina farmland and slaves to expand his

agricultural pursuits. This strategy culminated in his assemblage of the Mepkin

Plantation where along with his mercantile pursuits Laurens

earned a fortune.

As a businessman, Laurens was quite critical of British

intervention in the Colonial economy. Laurens was a party to frequent lawsuits

with the crown judges and had an exceptional understanding of law. Politically

Laurens was especially critical of British judicial decisions regarding marine

law. The pamphlets that Laurens authored and subsequently published in

opposition to the crown’s interference in Colonial trade are exceptional legal

accounts of Great Britain’s trade oppression of the Colonies.

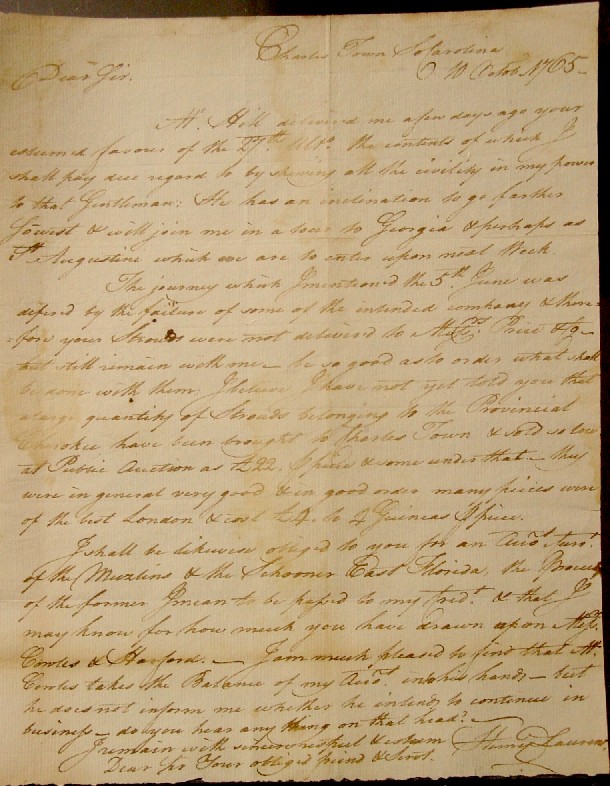

Autograph Letter Signed regarding financial matters

from Charleston on 10 October 1765. In this detailed, closely-written

business letter, Laurens tells of his plans to leave the following week on a

visit to Georgia and possibly St. Augustine; explains why he was unable to

deliver the strouds belonging to his correspondent (strouds were a coarse

woolen cloth used in trade with the Indians). Laurens asks what "shall be

done with them," adding "I believe I have not yet told you a large

Quantity of Strouds belonging to the Provincial Cherokee have been brought

to Charles Town & sold so low at Public Auction as 22 pds p[er] piece & some

under that. They were in general very good & in good order, many pieces were

of the best London & cost 4pds to 4 Guineas p[er] piece." Laurens

goes on to inquire about his accounts with his correspondent for "the

Muzlins & the Schooner East Florida," and asks whether a Mr.Cowles, with

whom he also has accounts, plans to remain in business. - Courtesy of the Author

Henry Laurens served in a military campaign against the

Cherokees. In this campaign he learned, first hand, on how to wage a battle in

the Colonial Wilderness. He took the time during that campaign to keep a diary

which still exists in its original manuscript form.

By 1771,

Laurens was so successful that he retired from business and sailed to England to

direct the education of his sons. During this period he traveled throughout

Great Britain and on the European continent. While in London he was one of the

thirty-eight Americans who signed a petition in 1774 to dissuade parliament from

passing the Boston Port Bill. Dismayed by the anti-colonial sentiment in

Great Britain, Laurens returned to Charleston that same year. Three months

later he was elected a member of South Carolina’s first Provincial Congress in

1775. He was elected President of that body in June 1775.

Delegate

Laurens drew up a form of association to be signed by all the Friends of Liberty

and also became President of the Council of Safety. He was elected a member of

the Second South Carolina Provincial Congress from serving from November 1775 to

March 1776. He also served as the president of the second council of safety and

was elected Vice President of South Carolina serving from March 1776 to June 27,

1777.

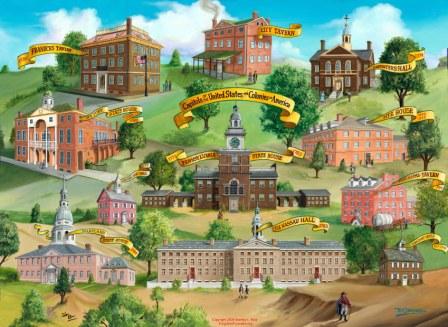

Laurens was

elected as a Delegate to the Continental Congress on January 10, 1777, and

served until 1780. During his initial term he was forced to flee Philadelphia

in the fall of 1777 to Lancaster. There he and his fellow delegates were unable

to find ample rooms in the district for either lodging or convening the

Continental Congress for more then one day, September 27th. Once again the

Continental Congress packed up and move the seat of Continental government just

across the Susquehanna River to a small village called YorkTown (now York,

Pennsylvania). The River was deemed a natural barrier to a British attack

providing the Continental Congress with plenty of time should British regulars

launch a second campaign to capture the Delegates. Henry Laurens' letter to John

Lewis Gervais on October 8th 1777 was particularly revealing of the freshman

delegate's flight from Philadelphia to Lancaster:

The Evening

of that day I went as far as Frankfort in order to see into the arrangement of

my baggage and to Shift my apparel Suitable to the change of weather & had

engaged to breakfast with an old friend at 1/2 past 8 next Morning in

Philadelphia. About 4 o'Clock next Morning I was knocked up by Sir Patrick

Houston who informed me that advice had been received of General Howe's crossing

Schuylkill at 11 o'Clock & that part of his Army would be in the City before

Sunrise. I could feel no impression, I judged differently from the City people

who I had always expected would fall a prey to their fears, I considered the

difficulty of crossing a ford with an Army of 6 or 7 Thousand Men, Cannon,

Horses, Wagons, Cattle &ca &ca, the right disposition of the whole & detaching a

respectable force to a distance of 22 Miles. While my Carriage & Wagon were

preparing to go forward the Scene was equally droll & melancholy. Thousands of

all Sorts in all appearances past by in such haste that very few could be

prevailed on to answer to the Simple question what News? however would not fly,

I stayed Breakfast & did not proceed till 8 o'Clock or past nor would I have

gone then but returned once more into the City if I had not been under an

engagement to take charge of the Marquis de Lafayette who lay wounded by a ball

through his Leg at Bristol. My bravery however was the effect of assurance for

could I have believed the current report, I should have fled as fast as any man,

no man can possibly have a greater reluctance to an intimacy with Sir William

Howe than my Self.

I proceeded

to Bristol, the little Town was covered by fugitives, the River by Vessels of

War & Store Vessels & others from Philadelphia, the Road choked by Carriages,

Horses & Wagons. The Same was disgustingly Specked by Regimental Coats &

Cockades, Volunteer blades I suppose who had blustered in that habit of the

mighty feats they would perform if the English should dare to come to

Philadelphia. Upon these I looked with deep contempt. From Bristol I had the

honor of conducting the Marquis who is possessed of the most excellent funds

[of] good sense & inexhaustible patience to Bethlehem where the Second day after

our arrival I left him in Bed anxious for nothing but to be again in our Army

as he always calls it, & proceeded through Reading to Lancaster, at Reading I

learned of General Wayne's false step, a second hindrance to our driving the

Invaders out of the Country.

Laurens, as a

freshman delegate, went right to work in YorkTown impressing the members of

Congress with his "nonpartisan" deliberations. His ideas especially

stood out on the creation of the first constitution of the United States, the

Articles of Confederation. Laurens remained steadfast against the nationalists'

proposal to allow control of the proposed new federal government by the wealthy.

He was also against Virginia's article to have one Delegate in Congress for

every 30,000 of a state’s inhabitants, permitting each representative having one

vote. On the Confederation Article that prohibited the federal government from

making any foreign treaty preventing the individual States "from imposing

such imposts and duties on foreigners as their own people are subject to",

Laurens was the only Southern member to vote against the measure. Unfortunately

only 3 other states, Rhode Island, New Hampshire, and Connecticut, voted with

Laurens so the restrictive Amendment became a part of the confederation

constitution shackling the future United States in Congress Assembled to

properly control and conduct foreign affairs.

In a usual

position Laurens voted for the United States in Congress Assembled to have the

authority to decide disputes between the states but then voted nay on the

establishment of the "elaborate machinery" necessary for such judicial

matters to be employed. This failure to separate the judicial duties of

government from the proposed legislative/executive federal body plagued the

United States until the adoption of its 2nd constitution in 1789.

Henry Laurens

in a final constitutional act, voted against Virginia's last attempt to gain

more power in the federal government based on population. Specifically,

Virginia's amendment proposed that the nine votes necessary to determine

matters of importance in the United States in Congress Assembled must be from

the states containing a majority of the white population in the new

"Perpetual Union". The measured failed largely because of Laurens and the

other smaller states objections.

This vote did

not follow the “southern block” clearly indicating Laurens was free from

sectional bias. Laurens stood out time and time again putting forth and

supporting articles and ideas that attempted to forge 13 individual States into

one unified nation. He envisioned and worked diligently to form a Constitution

that empowered a new central government to act for the benefit of all States

equally. This philosophy, unknowingly, made him a leading candidate for the

Presidency to replace the ailing John Hancock in 1777.

On October 29th,

John Hancock, resigned from the Presidency. The powerful Adams-Lee coalition

decided to back Francis Lightfoot Lee as chosen as Hancock's successor. Laurens

did not support the Virginian’s nomination moving that Congress solicit Hancock

to remain. The motion was only seconded and no failed to win a majority. To

Laurens astonishment, the Chair nominated him, a vote was taken and he became

the 2nd President of the Continental Congress of the United States of America.

This was a high

tribute as Laurens was a freshman delegate and not a signor of the Declaration

of Independence. Clearly, his character, independent thinking and businessman's

no nonsense approach to the confederation constitution impressed the Delegates

that Laurens could lead this fledgling nation to complete the 1st

Constitution of the United States andwin the war with Great Britain. Delegate

Roberdeau wrote:

"Henry Laurens, Vice President of South Carolina, a worthy, sensible,

indefatigable Gentleman, was this day chosen by a unanimous vote, except his

own, President of Congress."

Henry Laurens

was elected to the Presidency on November 1, 1777 and in letter to the Carlisle

Committee on the 4th he hints at one major reason for Hancock's resignation:

"Your Letter of the 22nd was duly received & taken under Consideration by

Congress.

The delay of a reply is imputable to the bad State of health of the late

president The Honorable John Hancock Esquire who having Suffered under the Gout

Several days before he retired from this place could not have discharged every

branch in his department with his wonted facility & precision."

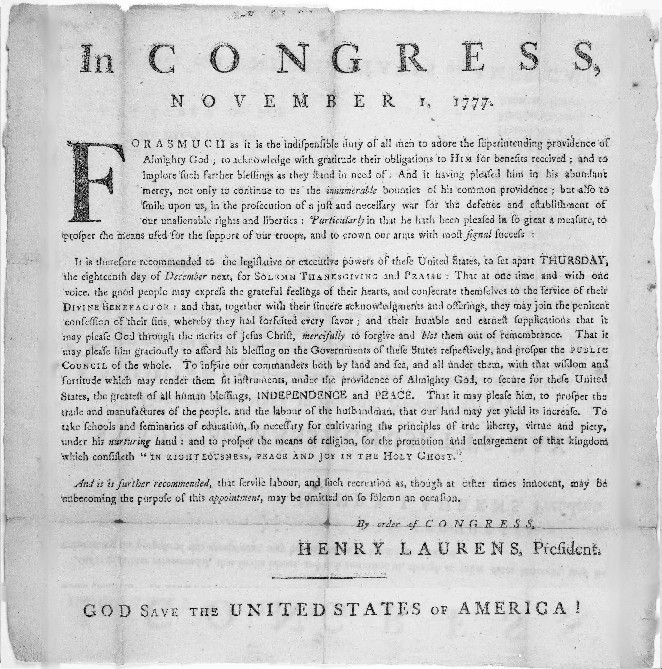

Henry Laurens

first official act as the President was to preside over and vote for a Day of

Thanksgiving and "to adore the superintending providence of Almighty God".

He was also a devoutly religious Christian. In his first letter to the States as

President he wrote:

"Dear Sir, The Arms of the United States of America having been blessed in

the present Campaign with remarkable Success, Congress have Resolved to

recommend that one day, Thursday the 18th December next be Set apart to be

observed by all Inhabitants throughout these States for a General thanksgiving

to Almighty God. And I have it in command to transmit to you the inclosed

extract from the minutes of Congress for that purpose.

Click on an image to view full-sized

Day of Thanksgiving

Forasmuch as it is the indispensable duty of all men to adore the

superintending providence of Almighty God; to acknowledge with gratitude their

obligation to him for benefits received, and to implore such farther blessings

as they stand in need of; and it having pleased him in his abundant mercy not

only to continue to us the innumerable bounties of his common providence, but

also to smile upon us in the prosecution of a just and necessary war, for the defence and establishment of our unalienable rights and liberties; particularly

in that he hath been pleased in so great a measure to prosper the means used for

the support of our troops and to crown our arms with most signal success: It is

therefore recommended to the legislative or executive powers of these United

States, to set apart Thursday, the eighteenth day of December next, for solemn

thanksgiving and praise; that with one heart1 and one voice the good people may

express the grateful feelings of their hearts, and consecrate themselves to the

service of their divine benefactor; and that together with their sincere

acknowledgments and offerings, they may join the penitent confession of their

manifold sins, whereby they had forfeited every favour, and their humble and

earnest supplication that it may please God, through the merits of Jesus Christ,

mercifully to forgive and blot them out of remembrance; that it may please him

graciously to afford his blessing on the governments of these states

respectively, and prosper the public council of the whole; to inspire our

commanders both by land and sea, and all under them, with that wisdom and

fortitude which may render them fit instruments, under the providence of

Almighty God, to secure for these United States the greatest of all human

blessings, independence and peace; that it may please him to prosper the trade

and manufactures of the people and the labour of the husbandman, that our land

may yet yield its increase; to take schools and seminaries of education, so

necessary for cultivating the principles of true liberty, virtue and piety,

under his nurturing hand, and to prosper the means of religion for the promotion

and enlargement of that kingdom which consisteth "in righteousness, peace and

joy in the Holy Ghost."

November 1, 1777 Thanksgiving Proclamation - Library of Congress, Rare Book and Special Collections

Division.

President

Laurens's office and lodging at YorkTown were not as large, he claimed, as the

center hall in his South Carolina home. Laurens noted he often dined on only

bread and cheese with a glass of grog which he believe appropriate with George

Washington and the soldiers at Valley Forge faring so much more worst. Laurens

learned the burden of the office very quickly being the conduit between Congress

and the have starved Commander-in-Chief. In addition to this Laurens was

responsible for the diplomatic correspondence, chairing the meetings, the

granting and refusal of favors to be heard by Congress.

In the first

part of December 1777 he, like his predecessor, had a severe attack of the gout

which confined him to his room. For the next three months he walked with a limp.

At the crisis over the Saratoga Convention he was carried into the YorkTown

Courthouse to preside over the crucial meeting. He wrote I am:

"… sitting eighteen or nineteen, sometimes twenty hours in twenty-four. This

encourages horrible swellings which are not quite dispersered with the short

respite in bed."

On December

12th, a mere 42 days after his election, he asked Congress to elect him a

successor. Laurens’ request was postponed by Congress, in a very complimentary

style, refusing to accept it. He then settled into the presidency for his

"year" term.

President

Laurens was an active participant in debate especially, when he the sole

delegate represented by South Carolina. His Presidency drew criticism by his

fellow delegates, as he was not hesitant to use his chair to make timely and

uncomplimentary remarks about his colleagues. As President, Laurens opposed any

expeditions against Florida urging Congress instead to defend Georgia and South

Carolina from Native Americans and Tory resistance.

In his book the

President of the Continental Congress 1774 - 1789 Jennings B. Sanders

writes:

Laurens is unique among the … Presidents … His letters give an insight into

the workings of Congress and the Presidential office … As President, he was

intimately acquainted with all Congressional affairs; indeed, many matters were

necessarily known only to him until their presentation from the chair.

Congressional leadership must not be construed to mean merely the activities of

members on the floor of that body. One gains the impression from a perusal of

the correspondence of the day, that important matters were discussed informally

outside Congress by coteries, fractions, and cliques as they ate their meals

together or visited their rooming places. Action in Congress, therefore, might

at times be little more than formal recognition of what had already been agreed

upon outside. Through this type of leadership a President might exercise great

influence, and yet never participate in debate from the chair.

For example,

Henry Laurens wrote on April 7, 1778 to James Duane that "… The Letter has

not yet been presented to Congress, but has undergone severe strictures from

knot of our friends who call here late at night and conned it over." On

another matter Laurens writes on April 28, 1778 concerning his reasoning for

delay of Louis Fleury’s petition "…these I say are private Sentiments drawn

from friends among my Coadjutors in Congress." The fact that the President,

for the most part, received all official correspondence gave him the discretion

to choose when and if it should be brought before Congress for consideration.

Laurens expertly utilized this power throughout his Presidency to accelerate or

impede the consideration of all official business of the United States of

America.

Henry Laurens

tenure as President was during one of most stormy periods in the Revolutionary

War. He seemed to align himself against John Jay, Robert Morris and Silas Deane

(conservatives) but kept his distance from the Adams-Lees Faction. A major test

of his “non-partisan” leadership erupted just nine days into his

Presidency. The plan for the displacement of George Washington for Horatio

Gates came to light on November 9th. The controversy then exploded

occurring during the same period that President Henry Laurens was occupied with

the Saratoga Convention, negotiating the surrender settlement of British General Burgoyne and his army. .

This scheme to

replace Washington stemmed from the Adams-Lees Faction, the "liberals",

who wanted to keep all executive business in the hands of Congress through

committees and boards. They strove for a strict system of control over the

Commander-in-Chief. The other faction is best described as the "constructive

party" and its leaders included George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, John

Jay, Robert Morris and Robert Livingston. The Adams-Lee Faction was comprised of

men who were the "Zealots" of revolution and forced altercation with

Great Britain. It was the constructive faction who transformed the fitful

rebellion into an organized and successful revolution. President Henry Laurens’

politics, however, was an enigma and thought by each camp to be partial to their

respective faction.

The Adams-Lee

Faction steadily worked, after General Gates' Victory at Saratoga, to bring

Congress to the opinion that the safety of the country demanded Horatio should

replace George as Commander-in-Chief. The plot, however, had few active

supporters in Congress. The Continental Army. chief supporters of the Gates

scheme, rounded off some impressive patriots supporting General Gates including

James Lovell, Benjamin Rush, General Thomas Mifflin and their organizer General

Thomas Conway, a French officer of Irish lineage. The movement to displace

Washington began before the Victory at Saratoga. Even John and Samuel Adams

contributed powerfully to hostility against George Washington by ridiculing his "Fabian Policy" calling for "a short and violent war" and

preaching according to Henry Laurens historian D. D. Wallace " … that the

worship of a man amounted to amounted to the sin of idolatry which would

certainly call down the curse of Heaven"

John Adams

exclaimed on the repulse of the British from Delaware River Forts:

"Thank God the glory is not immediately due to the Commander-in-Chief, or

idolatry and adulation would have been so excessive as to endanger our

liberties."

As the attacks on Washington mounted

the plotters made wild charges of his incompetence. It was asserted that

cowardice restrained Washington from driving General Howe out of Philadelphia in

1777 even though he had two to three times more forces than the British. For

example, James Lovell the delegate from Massachusetts maintained that Washington

marched his army up and down with no other purpose then to wear out their

clothing, shoes, and stockings. The facts on this particular case, however, were

that General Howe's foraging parties had greater numbers than Washington's

entire army encamped in Valley Forge. An attack on Philadelphia would have

decimated the Continental Army.

The Continental Congress, to make

matters more complex for Washington, bestowed upon Gates and his supporters a

series of appointments and promotions. Most notably, Generals Gates and Mifflin

were placed upon the Board of War and Conway was elected against Washington's

protest as Inspector General of the Continental Army. In these influential

positions the scheme to replace Washington was pressed forward by a series of

"interferences, shackles, vexations and slights to resign his command"

according to Revolutionary War Historian Wallace. Their incompetence of

managing the Board of War, Commissary and Quartermaster departments left wagon

loads of clothing and provisions standing in the woods much to the chagrin of

Henry Laurens. The now historic sufferings of Washington and his troops at

Valley Forge were due to these men's incompetence and burning desire to replace

the Commander-in-Chief with Horatio Gates. The Valley Forge tragedy was NOT

a product of the new nation’s poverty or the refusal of its citizens to

contribute to the War effort.

Irrefutable

proof of a conspiracy against George Washington came to light when General

Stirling sent the Commander-in-Chief a quote from Thomas Conway's letter to

Gates:

"Heaven has been determined to save your country, or a weak general and bad

counselors would have ruined it."

Washington’s

only response was to send the quote back to Conway on November 9, writing only: “A letter, which I received last night, contained the following paragraph.”

On November 28, Q.M. Gen. and

future President Thomas Mifflin sent a letter to Gates alerting him that the

extract from Conway’s letter had been sent to Washington, and how the

Commander-in-Chief responded. Mifflin’s letter indicated he agreed that Conway’s

letter was just. In this letter he cautioned Gates to be careful; as such open

correspondence will “injure his best friends.”

Washington never made this letter

public. Gates, however, did not heed Mifflin’s advice and wrote Washington a

letter ranting about a so called scoundrel who supposedly leaked the Conway

letter to the public. To Washington’s amazement, Gates copied Congress thus

making the letter public.

Henry Laurens

learned of this through his son, a Washington Aide-to-Camp. John Laurens wrote

to his father from headquarters on January 3rd, 1778 giving this assessment in a

brief sentence identifying the Cabal’s true “head”.

"Conway has weight with a certain party, formed against the present

Commander-in Chief at the head of which is General Mifflin."

General

Conway's letter gave George Washington no other option but to defend himself

openly against the conspiracy as it was now in the public eye. Washington wrote

to Laurens on January 4th, 1778 that it was “beyond the depth of

my comprehension” that Gates would make public the correspondence.

Washington wrote a letter to Gates and copied Congress notifying him that it was

his own aide, Wilkinson, who had been indiscreet and not anyone in his camp.

President

Laurens wrote to his son:

"Talking of General Conway's Letter which has been circulating as formerly

intimated, & of which General Gates declared both his ignorance &

disapprobation, I took occasion to say, if General Conway pretends sincerity in

his late parallel between the Great F____ [Fredrick] & the great W____

[Washington] he has, taking this Letter into view, been guilty of the blackest

hypocrisy - if not, he is chargeable with the guilt of an unprovoked sarcasm &

is unpardonable. The General perfectly acquiesced in that sentiment & added such

hints as convinced me he thought highly of Conway. Shall such a Man seperate

friends or keep them asunder? It must not be. My Dear son, I pray God protect

you."

Laurens was

anxious to play the role of "peacemaker" between Gates and Washington

walking the middle ground. In the end Laurens neutrality embolden the Cabal but

the scheme to replace George Washington with Horatio Gates fell apart in early

1778 when the plan was made public. One after another the delegates and

generals hasten to disclaim any connection to the Conway and Gates. The

reaction of the people was clear, George Washington was strongly entrenched in

the minds and hearts of the common man and they wanted him to remain the

Commander-in-Chief. The public's affection towards Washington did not

"endanger our libertieis" as Adams predicted but rather gave them new

support as the people rallied around the Commander-in Chief. The Cabal was dead,

the people had spoken this lesson culminated to finally combining the the office

of the U.S. Presidency with the power of Commander-in-Chief in the 2nd

Constitution of 1787. The 2nd Constitutional Convention in 1778 was

still 9 years away with the States still debating ratifying the 1st

Constitution, the Articles of Confederation. Despite Washington holding on as

Commander-in-Chief the country fell into desperate times over the divisive

philosophies in Congress on how to conduct business while it awaited the

ratification of the 1st Constitution. President Laurens' remarked

during this devise period that the fledgling confederation held together only

because the enemy "keeps pace with us in profusion, mismanagement and family

discord"

Despite the

challenges, Henry Laurens, remained positive turning to the business of the

Presidency. The "Conway Cabal" was now behind him, the Articles

of Confederation before the States for ratification, and the Victory at Saratoga

was a military coo so impressive that the French were now ready to sign a series

of Commerce and Alliance Treaties with the Continental Congress.

President Laurens, an astute businessman, believed that commerce provisions in

one of the treaties were seriously flawed. Specifically he objected to the

Confederation abandoning, by treaty, its claims over the control of Florida and

the Bahamas which were important future sources of federal revenue in trade

duties and land sales. Additionally Laurens believed that French interest in

these territories was political cautioning his fellow delegates that once the

treaties were ratified Spain would be lay claim to Florida. France would remain

neutral on Spanish land accession due to a clandestine "side" agreement

between the two European Powers. Laurens was heavily ridiculed by his peers and

out maneuvered on measures to correct these inadequacies.

The treaties

were executed on February 6, 1778 and despite his doubts, President Laurens

expressed a "most hearty congratulations" to Commissioners Silas Deane,

Benjamin Franklin and Arthur Lee. Time, however, proved Laurens right as the

United States loss the valuable southern port of St. Augustine and large tracts

of land which, were both direly needed to fund the fledging government.

In the spring

of 1778, Laurens letters spoke continuously of the deficiency of State

representation in Congress. He found fault in both the bare necessity of

delegates to make quorums and the inexperience of Congress. He believed the

inexperienced delegates were not capable of dealing with important commercial

treaties between America and Denmark, Russia, Spain, Holland and Sweden. He

ardently sought more experienced representation from the state legislatures in

numerous letters to their leaders.

By the summer

of 1778 his letters blossomed into the formation of a considerably strengthened

Congress. Samuel Adams returned after an absence of six months. Gouvernor Morris

and Roger Sherman also returned along with Thomas Heyward. The brilliant young

William Henry Drayton, Richard Hutson and John Matthews all took their seats in

YorkTown.

The Conway

Cabal emerged once again in the summer of 1778 when Thomas Mifflin, a general

who sided with Gates against Washington, was addressed as "pivot" in this

Laurens letter to his son in June. In this letter Laurens writes about

Congress's call for an investigation into General Mifflin's quartermaster

activities:

"If you were here in this Room I could entertain you five minutes with

description of an excellent attempt in favor of pivot which was not only ousted

but brought on a proposition which, as a Man of honor he must have wished for,

as a Man of politeness he must have wished for it, because all the World wished

for it. Your antagonists I find have not yet turned their backs, the more

motions they make the more I suspect them. When they shall be fairly gone I

will sing te deum, but 'till then my duty & my Interest dictate infidelity &

command me to be watchful. The long continuance of repeated accounts marking

their intended embarkation has injured our Cause more than you are aware of.

Adieu."

Laurens

according to the Library of congress

"… was

alluding to the call for an investigation of former quartermaster general Thomas

Mifflin that Congress approved this day."

In previous

correspondence with his son, Laurens had used the term "pivot" to

designate Mifflin's role in the so-called Conway Cabal. That John Laurens

understood the use of it in the present letter as a reference to Mifflin is

indicated by this statement in his June 14th reply:

"The inquiry into the conduct of the late quarter masters, must give pleasure

to every man who wishes to see the betrayers of public trusts brought to condign

punishment."

General Mifflin

would later be exonerated of these charges and go on to serve as President of

the United States in Congress Assembled. George Washington, however, remained

cool to Mifflin throughout the rest of his days never forgetting his role in the

Conway Cabal. In an ironic twist a fate when George Washington finally resigned

his office of Commander-in-Chief in 1783 it was done ceremoniously to the

President of the United States, Thomas Mifflin.

October 31,

1778 marked Laurens completion of his one-year term prescribed in the

un-ratified Articles of Confederation. Laurens had often referenced

his approval of the Confederation Constitution’s provision forbidding a delegate

to hold the Presidency more than one year in three and accordingly he offered

his resignation. The constitution, however, was not ratified and no Perpetual

Union or it governing body, the United States of America in Congress

Assembled, was formed. The Continental Congress still existed and operated

under the Articles of Association so Laurens was not required to step

down from this presiding office. It was reported that the members gathered in a

circle to discuss his resignation and Samuel Adams communicated their unanimous

desire for Laurens to serve until the Articles were ratified by all the States

creating the new United States of America in Congress Assembled. Laurens

according to biographer D. D. Wallace:

"Expressed his pleasure at being able to balk 'his quondam friend' in the

newspaper and acceded to the request of the members, but declined to approve a

minute of the proceedings saying 'he had no anxiety for obtaining complimentary

records.' The Journals thus contain no suggestion of the incident."

The Deane-Lee

foreign affairs controversy also fell into the lap of President Laurens. Silas

Deane was one of the commissioners who negotiated the February Treaty with

France. Deane had also contracted the services of Lafayette, De Kalb, and other

foreign officers, personally, to the cause for Independence. These contracts

were subsequently made the basis of charges against him by congress on the

grounds of extravagance. Deane was recalled in consequence by resolution passed

and signed by Laurens.

Reaching

Philadelphia in 1778, Deane found that many reports had been circulated to his

discredit. These seem to have originated with his late colleague, Arthur Lee,

who had quarreled with him in Paris. Henry Laurens received Deane and went over

all his affairs in a two-hour private interview. Henry Laurens reported that he

believed Dean supporting his account.

Deane had

presented a signed statement from Grand, the commissioners' Paris Banker, of all

funds spent. Banker Grand, however refused to part with the original vouchers

until the final accounting. President Laurens found this inappropriate as Deane

had disbursed 250,000 pounds sterling and had no excuse for coming without

accounts and vouchers. Arthur Lee reiterated his charges and Deane's advocates

failed to rally his cause squarely before Congress causing Lauren's to side

against Silas Deane.

A Congressional

inquiry into the state of foreign affairs also included a thorough examination

of Mr. Deane's role. He was regularly notified to attend the sessions in an

attempt to discern the facts of the controversy. On December 4th Deane wrote

again to Congress, acquainting them with his having received their notification

of another session and expressing his thanks for the ongoing investigation. On

the following day, to almost everyone's surprise, Deane published his

extraordinary address in the Pennsylvania Packet, which attacked

Congress, President Henry Laurens and his accusers.

More on Henry Laurens Click Here

Click Here

In this powerful, historic work, Stan Klos unfolds the complex 15-year

U.S. Founding period revealing, for the first time, four distinctly

different United American Republics. This is history on a splendid scale --

a book about the not quite unified American Colonies and States that would

eventually form a fourth republic, with

only 11 states, the United States of America: We The People.